Written by Caroline E. Smith, Esq.

The U.S. District Court for the District of Massachusetts issued an important decision in the case of Valentin v. Town of Natick et al., 2022 WL 4481412 (D. Mass. Sept. 27, 2022). This federal court litigation arose from the denial of an application for a permit to develop a condominium project that included affordable housing in Natick, Massachusetts.

The Plaintiffs are the Valentins, a black couple who have lived in Natick for thirty years. They proposed a condominium project to be located in a predominantly white neighborhood and were denied. Plaintiffs filed suit alleging discrimination based on race, color, and national origin.

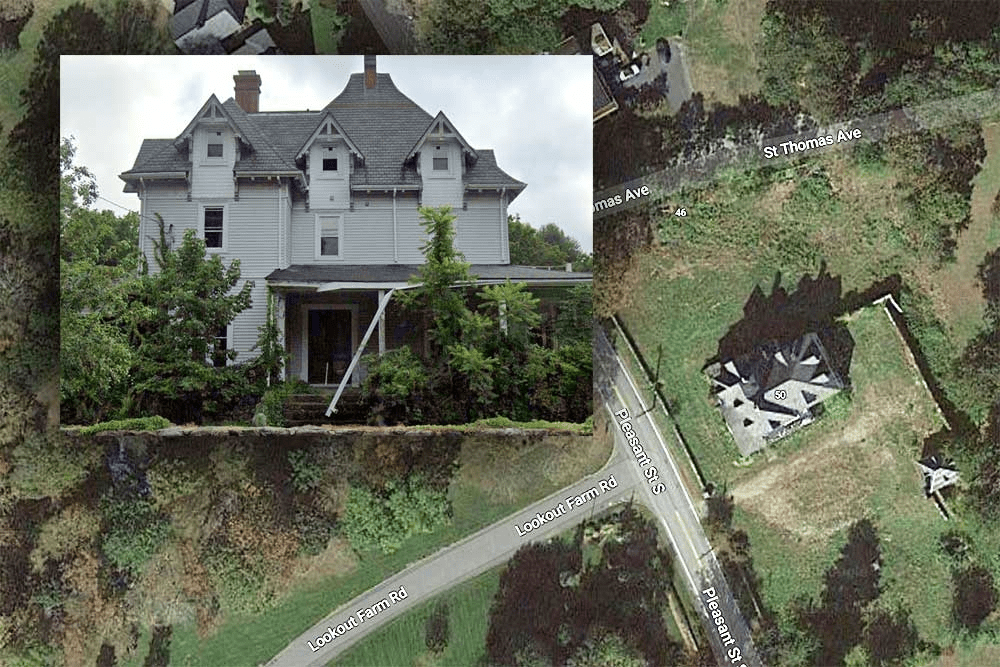

In 2005, the Valentins bought the historic property in Natick that is the subject of this suit. In early 2019, the Planning Board (the “Board”), with the help of the Valentins, developed Natick’s Historic Preservation Bylaw (the “Bylaw”). The Bylaw passed Town Meeting with a vote of 96 to 4.

On August 28, 2019, the Valentins applied for a special permit and site plan approval under the Bylaw. The Valentins proposed to renovate the existing historic house on the lot, reconstruct the historic barn and carriage house, put in underground parking, and add eleven condominium units (including affordable housing units). The proposal complied with all the dimensional requirements of the Bylaw.

The Board was initially in favor of the proposal. However, after neighbors began a campaign against the project, including allegedly racist comments, the Board back-tracked and requested a revised plan from the Valentins.

In the fall of 2019, the Valentins submitted a revised plan that eliminated the carriage house and one condominium unit. At the Board meeting to review this revised plan, the Board expressed confusion over how to interpret the Bylaw.

In December 2019, Town Counsel issued an opinion that the revised plan did adhere to the Bylaw. The Board did not take that advice of Town Counsel, however, and instead determined that the Bylaw restricted the project further. In January 2020, the Board suggested to the Valentins that they withdraw their application without prejudice. The Valentins did withdraw.

On February 24, 2020, the Valentins renewed their application under the Bylaw. By this time, the neighbors had begun their own campaign to repeal the Bylaw.

On April 22, 2020, the Board declared two new interpretations of the Bylaw, which had the effect of reducing allowable new construction by one-third. Based on these new interpretations, in October 2020, the Valentins submitted yet another revised plan which reduced the number of condominium units from eleven to seven.

At the same time, the Chair of the Historic Commission forwarded to the Board neighbors’ concerns that the project was too big. The Chair also endorsed the repeal of the Bylaw. In response to the Valentins’ questions, the Town assured the Valentins that their project would be “vested” (formerly known as grandfathering), and thus would be allowed to proceed even if the Bylaw were repealed.

On November 4, 2020, the Board voted to approve the massing, scale, and layout of the Valentins’ project, but did not vote on whether to grant the special permit. On November 10, 2020 the Town voted to repeal the Bylaw.

On December 2, 2020, the Board denied the Valentins’ application solely on the basis of the repeal of the Bylaw. The Board did not consider the project “vested,” despite previously having indicated that it would receive such protection.

The Plaintiffs made a federal case out of it. They sued under the Fair Housing Act (“FHA”), 42 U.S.C. §§ 3604 and 3617; 42 U.S.C. § 1983 for violations of their constitutional rights to Equal Protection (“EP”); Substantive Due Process (“SDP”); and Procedural Due Process (“PDP”). They also asserted claims against the individual defendants under the Massachusetts Civil Rights Act (“MCRA”), Mass. Gen Laws c. 12, § 11H.

The Defendants filed a motion to dismiss all the claims. The federal District Court decision carefully parsed those claims and defenses and opened a window into when, how and under what conditions such civil rights claims can be successfully asserted.

First, the Court considered Section 3604 of the FHA prohibits discrimination in housing based on race, color, and national origin. In order to prove a violation of the FHA, a plaintiff must show either discriminatory intent or disparate impact. A plaintiff must allege that:

(1) she is a member of a protected class;

(2) she applied for a permit and was qualified to receive it;

(3) the permit was denied despite the plaintiff being qualified; and

(4) the defendant approved the same type of permit for a similarly situated party during a period relatively near in time plaintiff was denied her permit.

The federal District Court easily found that the Valentins alleged (1), (2), and (3). As for (4), the Valentins alleged that the Town had granted a permit for a church project that was similarly situated because it was a conversion of a historical building in a residential neighborhood into condominium units.

The church project had been proposed under the 2014 bylaw and not the new Bylaw under which the Valentins applied. The District Court, however, held that the sequence of events and procedural treatments of the two projects was sufficient to provide circumstantial evidence of discriminatory intent.

The Valentins’ FHA 3604 claim thereby survived the motion to dismiss.

Secondly, Section 3617 of the FHA makes it unlawful to coerce, intimidate, threaten, or interfere with any person in the exercise or enjoyment of rights granted under § 3604 (above). To prevail on a claim, a plaintiff must show:

(1) she is a member of a FHA-protected class;

(2) the plaintiff exercised a right protected by §§ 3603–06 of the FHA;

(3) the defendants’ conduct was at least partially motivated by intentional discrimination; and

(4) the defendants’ conduct constituted coercion, intimidation, threat, or interference on account of having exercised, aided, or encouraged others in exercising a right protected by the FHA.

Again, the federal District Court easily concluded that the Valentins met (1), (2), and (3). The Valentins alleged that the Defendants delayed the project, asked for and ignored expert opinions, and misrepresented the consequences of the bylaw repeal on the project. The District Court found these allegations were sufficient for a claim that the Defendants interfered with the Valentins’ rights.

This FHA 3617 claim likewise survived the motion to dismiss.

Thirdly, the Court considered Plaintiffs’ Equal Protection Claim. The Valentins argued that the Board violated their equal protection right by effectuating the discriminatory intent of the neighborhood by raising procedural hurdles to slow down the permitting process. In support of this claim, they alleged that the Board reversed course on them three times, namely:

the Board initially looked favorably upon the project, but the reversed course once the neighbors began their campaign against the project;

The Board developed and support the Bylaw and then labeled it confusing and unclear; and

The Board assured the Valentins that their project would be vested and then said the bylaw appeal applied to pre-existing proposals.

This EP claim thereby survived the motion to dismiss. The federal District Court ruled that the Valentins stated a plausible claim that the Town’s actions were in violation of their equal protection rights.

Fourthly, the Court addressed the Valentins’ Substantive Due Process claim. A claim of this sort, under the principles of many First Circuit decisions, may be brought in federal court where the alleged abuse of power ”shocks the conscience.” The usual land use decision making disputes in Massachusetts and New England, even with anomalies and bad feelings, do not rise to this level of civil rights violation. A planning dispute tainted with procedural irregularity and racial animus, however, might be ruled in court to shock the conscience.

This SDP claim did survive the motion to dismiss. The federal District Court held that the Valentins had “plausibly alleged procedural irregularities in the number of hearings and delays, along with acquiescence to the racist opposition sufficient to state a substantive due process claim.”

Fifthly, the Court reviewed Plaintiffs’ Procedural Due Process claim. The Valentins had appealed the denial of the special permit to the Land Court pursuant to the Massachusetts Zoning Act, M.G.L. c. 40A, § 17 and then had voluntarily withdrawn their appeal. The federal District Court in this circumstance held that the judicial review afforded under § 17 was a sufficient post-deprivation remedy.

This PDP claim, consequently, was dismissed.

Finally, the Court turned to the Valentins’ claim under the Massachusetts Civil Rights Act. This important state statute provides a cause of action against any person who interferes or attempts to interfere with the rights of another by threats, intimidation, or coercion.

As discussed above, the federal District Court held that the Valentins had plausibly alleged that defendants interfered with their rights. In order to survive a motion to dismiss on their MCRA claim, however, the plaintiffs also had to allege that the interference was by “threats, intimidation, or coercion.” The Court held that a prolonged hearing process was not intimidation or coercion.

The Court therefore dismissed the Valentins’ MCRA claim.

In sum, the Valentins’ Fair Housing Act, Equal Protection, and Substantive Due Process legal claims all survived the Town of Natick’s motion to dismiss, while their Procedural Due Process and Massachusetts Civil Rights Act claims were dismissed.

All in all, this is a significant win for the Valentins and advances federal jurisprudence on the rare situation where municipal land use permit disputes are ruled to rise to the dignity of civil rights claims.

As of this writing the case is in the discovery phase and those surviving claims will proceed toward trial.